By Paschal Norbert

NOVEMBER 19, 2024 (CISA) – The growing discontent with President William Ruto’s administration is undeniable. Elected nearly three years ago as the self-styled “Hustler President” championing the cause of the poor, his tenure has been marked by policies and initiatives that have left many Kenyans disillusioned and financially strained. Promised reforms in health care under the Social Health Authority (SHA) are floundering. The education sector is in disarray, the affordable housing project has stalled, and the much-touted Hustler Fund has seen widespread defaulting.

The lavish lifestyle of the president and his inner circle only deepens public resentment. A leader described as a “master of half-truths” has yet to fulfill many of his roadside promises, leaving ordinary citizens to grapple with an ever-widening gap between the rich and poor. To make matters worse, a culture of entitlement among the wealthy, many with dubious origins of affluence, seems to mock the struggles of the impoverished. This is in stark contrast to the Catholic Church’s social teaching on preferential treatment for the poor, which remains more preached than practiced, even within the clergy and episcopate.

Amid this societal turmoil, the Church finds itself at a critical juncture, navigating a tense, simmering storm. However, I am not surprised because the Catholic Church has been here before. When the politics of the state and its citizens collide with the politics of the Church and its hierarchy, the resulting tension reveals deep fault lines within both institutions. These interactions expose not only the challenges of governance and leadership but also the shared struggles of integrity, accountability, and moral authority.

Historically, the Catholic Church has been a beacon during national crises, but internal contradictions, corruption, tribalism, misplaced priorities, and mismanagement that also exist within the Church, reflect the very issues plaguing the country. The Church, a mirror of society, must hold itself accountable alongside its prophetic critique of the state.

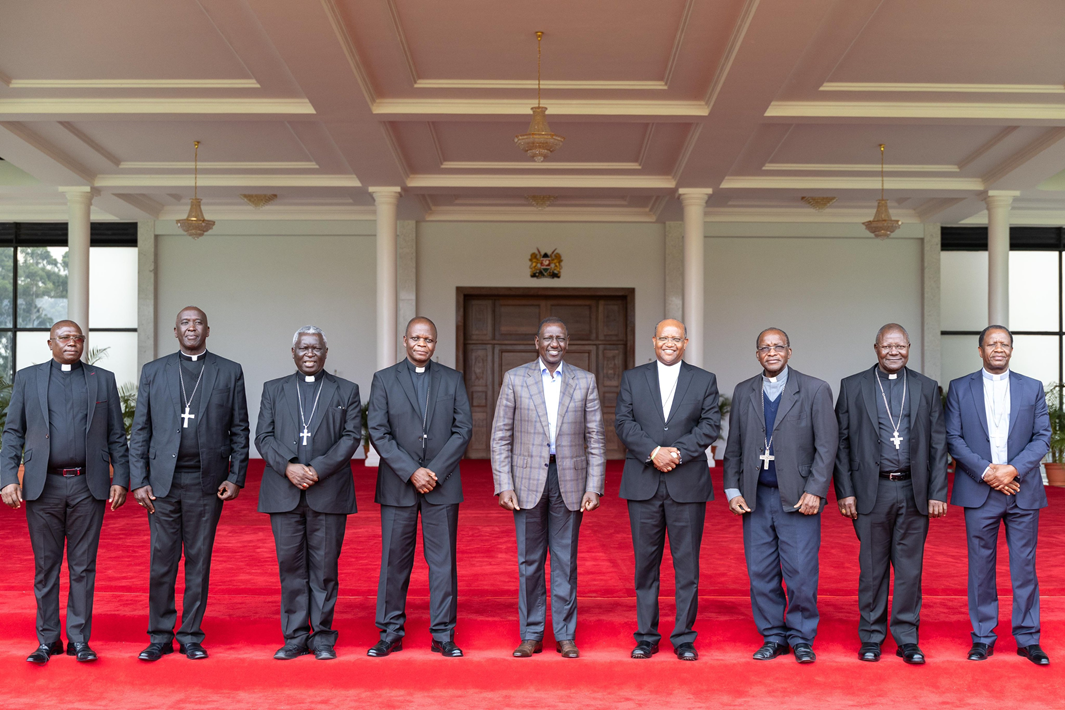

On November 14, our bishops issued a strong statement condemning the government’s broken promises, the oppressive tactics of its administration, corruption and its misplaced priorities. This bold move stems from the cries of the faithful-ordinary Kenyans whose prayers seem unanswered amid relentless hardship. In the statement, the bishops acknowledged their past camaraderie with the government but admitted that the gamble had failed, leaving them to confront the bitter reality of unfulfilled hopes. They sensed it deeply, perhaps they had placed too much trust in this government, wagering on promises that have now come undone. The gamble has failed, and the returns are nonexistent; the hope invested is yielding nothing but disillusionment.

Faith-based health centers are struggling to provide affordable care due to unpaid bills by the now defunct NHIF, with some resorting to layoffs. Even missionaries are now burdened with exorbitant fees due to the steep hike in work permit costs, making it increasingly difficult and costly to carry out their evangelization efforts within Kenya’s borders. Yet, through their efforts many have been educated, lives changed and communities have risen from the dust.

The bishops’ statement has inspired other religious groups: Anglicans, PCEA, and Muslims, to echo their sentiments in calling out this government. However, the Church must tread cautiously. The state and Church are deeply intertwined, each needing the other, but this relationship requires balance, not submission.

This moment calls for introspection among the bishops. The episcopal conference is relatively young, with many bishops in their sixties. While ambition is no sin, it must be tempered by wisdom to prevent the kind of divisions seen in 2007, which ultimately impacted the faithful. What the Church needs now is clear direction, not internal cold wars. Moreover, it must resist the temptation of being drawn into political schemes, as recently witnessed in Embu.

As the older generation of bishops gradually steps down, many new bishops, including archbishops, are taking leadership roles in key dioceses. This shift provides the new local ordinaries more influence within the local Church and among the faithful, impacting political, economic, and administrative aspects of the dioceses and regions they represent.

The traditionally conservative older bishops are finding themselves outpaced by changes in faith, evangelization, evolving maturity of the faithful, and emerging questions about Church practices. In contrast, the younger bishops, who are increasingly challenging the status quo, bring fresh perspectives. Theirs is a breed not seen in recent years and a blend between both the diocesan and missionary backgrounds. Many are former and pioneer African superiors of various missionary congregations that have played a significant role in evangelizing Kenya.

This generational shift, however, welcomed by many poses a challenge to established traditions and the old guard. The recent appointments of younger bishops with innovative ideas is amplifying this dynamic.

Senior bishops should also resist the lure of performative politics. Social media, while a powerful feedback tool, can easily become a trap where well-intentioned leaders are buried under public criticism. The focus should remain on service, not spectacle.

A recent example underscores this dilemma. On November 18, the Archdiocese of Nairobi issued a statement rejecting financial support from the president and his delegation intended for building projects and community support at Sts. Joachim and Anne Parish SVD in Soweto to build a priest’s house, support the choir and children.

However, the statement inadvertently referenced a proposed bill yet to be enacted into law, creating the impression that the Church supports it without fully understanding its implications. This misstep raises concerns, as the bill could potentially target the Church, making it a victim of the very policies it unintentionally endorsed. With many Church projects heavily reliant on fundraisers and funds raised by the faithful, who include politicians as practicing Christians, the unintended consequences could be significant. These politicians, after all, are not lesser Christians themselves.

While one can argue that Nairobi can afford to decline such aid, many dioceses cannot. This raises difficult questions: Should all donations from politicians be rejected, even those made discreetly? What about contributions from Catholic politicians or donations that genuinely support development projects? Will the Church and bishops also commit to declaring the funds they receive from politicians or other influential sources, whether publicly or privately? Transparency must apply universally if the Church is to maintain its moral authority. It must clarify its stance, ensuring transparency and consistency.

Truthfully, many parishes and even entire dioceses are struggling to sustain themselves, support their staff, or provide for their priests. While the Catholic Church in Kenya is one of the most vibrant and influential in the world, second only to Nigeria, several dioceses are still in the initial stages of evangelization.

This disparity was highlighted by the Apostolic Nuncio, Archbishop Bert van Megen, during St. Luke Deanery Kabete Family Day on October 26. Addressing the imbalance among dioceses, parishes, and clergy, he remarked, “During the Synod discussions, the question of money arose repeatedly, with many calling for greater transparency and accountability. If we demand these virtues from the government, we must first practice them ourselves.”

The Nuncio pointed to the inequities in resource distribution within the Church, advocating for clear and fair financial rules: “In Holland, priests do not directly handle money. Parish councils manage finances, and the diocese determines salaries, neither a penny more nor a penny less. This ensures equity. In Kenya, there is a stark contrast: priests in wealthier deaneries like Kabete may have ample resources, while those in remote regions such as Marsabit or Lodwar often struggle to survive. We need a system that distributes income and resources equally, so no priest is disadvantaged based on location. Period!”

His call for fairness underscores the urgent need for reform within the Church. Despite these challenges, the Church in Kenya has taken a bold stand, reaffirming its role as a prophetic voice for the voiceless. We pray that our shepherds remain steadfast, resisting distractions such as public controversies or the enticements of political power, to focus on their mission of service and justice.